Dunes pictures worth a thousand years

Authored by

Mental, photographic mapping meant to protect Michigan ecosystems for centuries

One summer morning in 2019, Kevin McKeehan, a Ph.D. candidate in Geography at Michigan State University, jumped into Lake Michigan. North Manitou Island was in full frame before him. Behind him, Capt. David Schroeder of the National Park Service turned his ship, the “Nahma,” away toward Lower Michigan’s mitten tip.

After wading to shore, McKeehan spent hours hiking, passing the occasional hollowed homestead of 19th-century loggers and fruit farmers.

Finally, the MSU graduate student found his destination: an outlook onto the island’s westward coastal dunes system.

It nearly matched the 1905 photo he had brought with him. But whereas the old picture depicted dunes with open sand at their slip surfaces and bluffs, the dunes before him were nearly covered in vegetation.

McKeehan snapped a picture, then waited for the “Nahma” to pick him up.

North Manitou Island was one of many stops for McKeehan as he sought to map the recent changes of Michigan’s coastal dunes through a practice known as repeat photography. He and MSU Department of Geography, Environment, and Spatial Sciences professor and chair Alan Arbogast spent weeks searching for old photographs of dunes in the archives of colleges, governmental departments and historical societies. Then, McKeehan would go out along Michigan’s western coast, taking pictures of the dunes from the same location others did decades ago.

“It proved to be difficult because of the nature of the dunes itself,” McKeehan said. “They change. Even when they are more stabilized with vegetation, they change.”

His work was part of the report “Learning to Live in Dynamic Dunes,” published this spring. It was the third cycle of collaboration between Michigan Environmental Council, MSU and many other organizations. The project’s three cycles have each been funded by the Coastal Management Program of Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy, in turn funded by a U.S. Department of Commerce grant.

See our social, photographic report

Read our economic, geographic report

The groups’ goals were four-fold. First, to mark the recent historical changes in the dunes’ fluid nature. Second, to create and add to the most detailed physical and mental maps of Michigan’s coastal dunes. Third, to educate people about the largest freshwater coastal dunes system in the world. Fourth, to use science-based research and education to help inform future policy decisions that benefit dunes, those that visit them and those that live around them.

“The collective ‘we’ needs to do a better job assisting and helping to inform local township and local municipality planning decisions when it comes to infrastructure along the shoreline,” said Tom Zimnicki, a program director for Michigan Environmental Council who led the most recent joint project.

Mapping the centuries-old, ever-changing dunes photographically, mentally and through GIS, Zimnicki said, is a unique way to help.

Mapping one’s mind out

As McKeehan traveled Michigan’s coast for photos, MSU Department of Community Sustainability professor and associate chair Robby Richardson and graduate student Laura Young guided west Michigan residents through mental modeling a few miles away from Saugatuck’s Mount Baldwin dune.

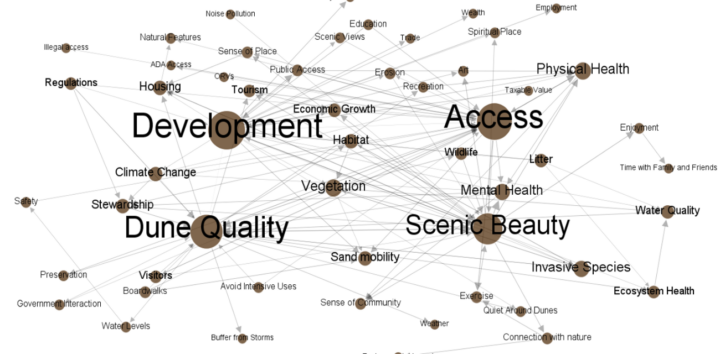

He first explained four components intrinsic to Michigan’s dunes, — quality, scenic beauty, access and development. Then, he had participants brainstorm other components, such as erosion, recreation, vegetation, and tourism. Next, Richardson asked them to determine the positive and negative association the components had with each other. Richardson then repeated this process at three other Michigan locations.

The result, a few months later, were 72 web-like maps of citizen scientists’ economic, environmental, cultural, even spiritual perceptions of Michigan’s 230,000 acres of coastal dunes systems.

“It’s a useful way of collecting information about how people perceive the value of the dunes and the threats to dune ecosystems,” Richardson said. “It’s a useful, visual way to illustrate how people think and how strongly they feel.”

Richardson’s work built off a survey on perceptions toward Michigan’s dunes 3,600 people took as part of the 2017 report between the Environmental Council, MSU, West Michigan Environmental Action Council, Heart of the Lakes and Ducks Unlimited. That, in turn, built off a joint 2015 report, which brought in dozens of other stakeholders—such as Calvin University—to create a GIS map of Michigan’s coastal dunes.

“The online survey gave us a little bit of information about what a whole lot of people think,” Richardson said. “The mental modeling allowed us to dig deeper into their perspectives and understanding, develop a more comprehensive and shared understanding of the dunes ecosystem and threats to those ecosystems.”

Arbogast believes physical, mental and photographic mapping projects over the past five years are thought to be the most detailed maps of Michigan’s coastal dunes ever constructed. Together, they create pictures worth a thousand years. This educational, scientific grounding has given researchers a better understanding of dunes’ centuries-old existence, and it presents future leaders the foundation they need to make informed decisions regarding dunes and the places around them for centuries to come.

Protecting centuries-old sand through science

Policy grounded in science is especially important given the dynamic, ever-shifting nature of dunes.

During the course of his long career, Arbogast has learned that the overall character, evolution, and behavior of the dunes is generally poorly understood by the public, despite their overwhelming popularity. Dunes are fluid features when free, being moved, stacked and shaped by wind. They tend to stabilize, however, when vegetation expands.

“I want people to understand the true nature of these systems so they can make informed management decisions based on facts,” Arbogast said.

Arbogast has studied Michigan’s coastal dunes for more than 20 years, adding to other scientists’ understanding of how the dunes evolved over the past approximately 5,000 years of geologic time. The collective body of this research demonstrates that the dunes have undergone distinct periods of activation at some points in the past, whereas they have been very stable at others. Evidence suggests that these changes seem to be related to variables such as prehistoric lake-level fluctuations, changes in storminess and climate changes. Given the statistical uncertainties in dating methodologies, however, it is not possible to discover the definitive character and associations of past behavioral changes in the dunes at even century-long time scales, let alone decades.

The repeat photography was meant to provide insight to those changes by examining the dunes at selected places during the photographic record, Arbogast said.

The final 25 repeat photographs that made the 2019 report often showed a progression toward more highly vegetated dunes systems.

That is not necessarily bad, Arbogast said. It was an indication that the dunes are generally becoming more stable, but not necessarily destroyed, by human development. The more open dunes are, the less vegetation they tend to have.

Richardson’s mental mapping indicated that, generally, people did not like vegetation on dunes – it made them harder to access and, at times, less scenic.

Coupled together, the photos and models could give municipal planners and councilmembers the information they need to decide whether development around dunes systems is best for what their constituents want, Zimnicki, of Michigan Environmental Council, said.

“At the end of the day, it’s harder to refute numbers,” Zimnicki said. “It’s harder to refute images. I think us doing that kind of work is really valuable to transfer it into state policy, and it could not have been done without the unique collaboration between groups that care about dunes and about novel science.”

Discover

Power environmental change today.

Your gift to the Michigan Environmental Council is a powerful investment in the air we breathe, our water and the places we love.

Sign up for environmental news & stories.

"*" indicates required fields